As Alaska Native corporations celebrate the value of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) in its first half century, Koniag will be sharing stories throughout the year highlighting ANCSA at 50 Successes.

The year was 1971. Dirty Harry and Shaft were in movie theaters, the Baltimore–not Indianapolis–Colts won the Super Bowl, and the Milwaukee Bucks won the NBA title. Half a world away in the community of Larsen Bay on Kodiak Island, a place with no movie theater or professional sports team, Jack Wick (no relation to the movie character) was fishing and working toward a private pilot license. Jack was just home from the Vietnam War and was unaware of the seismic shift for Alaska’s Native people and their land that he was about to become a part of.

The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) was being written in the halls of Congress, thousands of miles away from Alaska, where not even Nostradamus could have foreseen its transformational impact on the young state and its Alaska Native communities. Alaska Native corporations, created by ANCSA, would soon become a major economic force, and Jack would go on to become a President and Board Member of the Koniag corporation. But he would first find out about ANCSA like he learned about most things: through fishing. Jack had been home and out of the service for about a month, and was hearing about ANCSA from other Alaska Native people working the sea. When his parents, Charles and Clyda Christensen, asked him to run for the Koniag Board, he was surprised to learn that he was a favored candidate.

“I asked what my chances were and they said they already talked to most of the tribal leaders and I was who they wanted. I was a little bit nervous,” Jack said.

It’s important to remember that this was a time before cell phones, computers, and email. Legislation impacting more than 150,000 Alaska Native people was being crafted a world away. Women and men like Jack were being asked to create entirely new lifestyles in the time it takes from summer to become winter.

ANCSA represented a groundbreaking policy change away from the lower-48 reservation system. It was the first time Congress and the federal government communicated that Indigenous people were capable of managing their own assets. It shattered two centuries of Congressional norms, establishing an approach that would enable stronger self-determination for Alaska’s first people. ANCSA divided the state into twelve distinct regions, mandating the creation of twelve private, for-profit Alaska Native regional corporations and over 200 private, for-profit Alaska Native village corporations owned by Alaska Native shareholders. Unlike in the lower-48 states, ANCSA’s foundation was in Alaska Native corporate ownership.

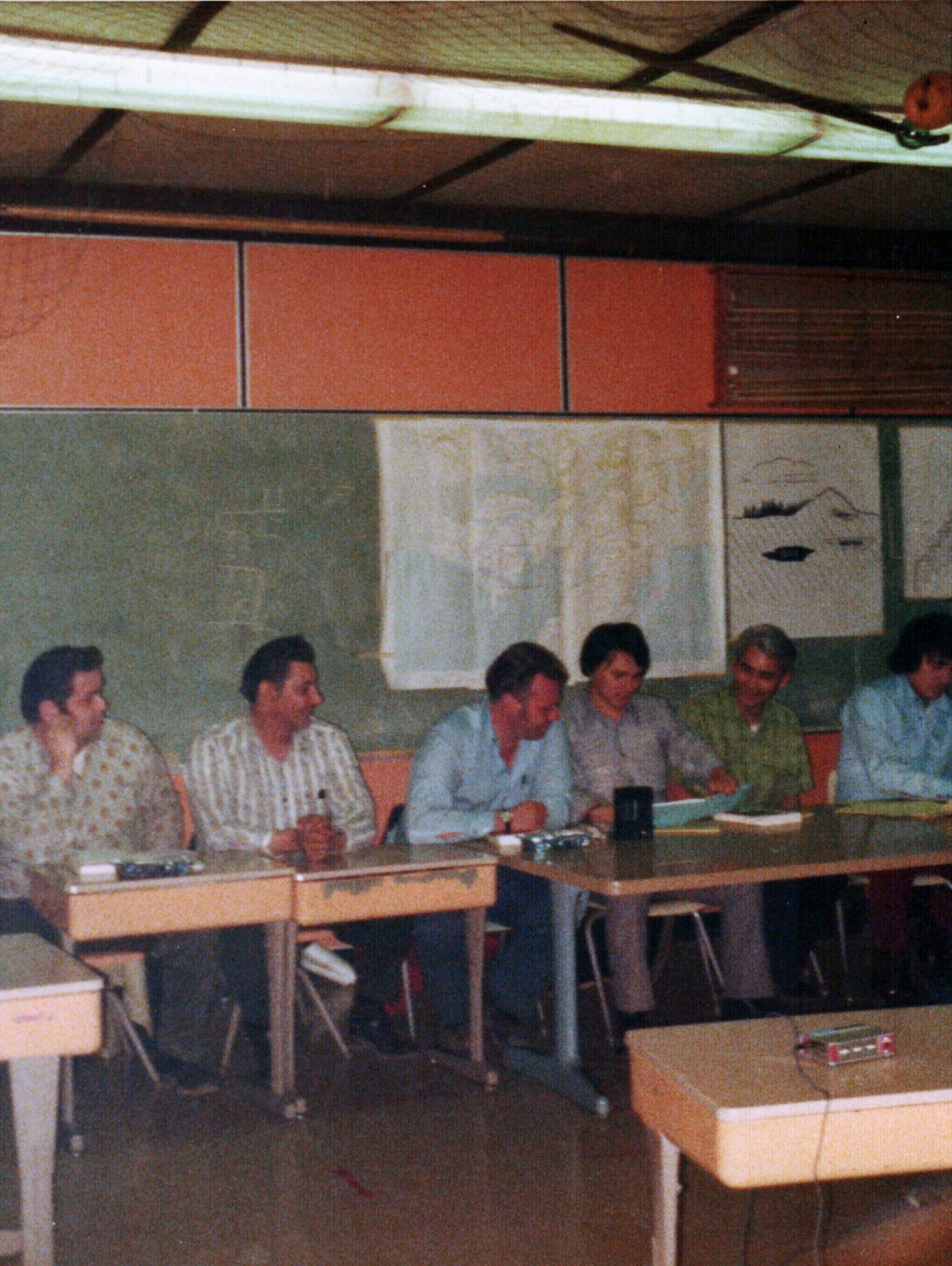

“It was exciting, and terrifying, we had to walk both sides of the fence in totally different worlds. Jack was the right guy, a leader and a Bronze Star winner,” remembers Perry Eaton, Jack’s best friend and another early Koniag Board Member. “Nobody knew what a corporation was. That is a lot of responsibility for people 20-some-years old to take on,” Eaton said. “We knew how to run a small business, but the world of a corporate board structure was totally new to us.”

Jack and Perry saw the struggles firsthand. “We lived off the land for most of my life,” Jack said. “My family and my friends fished; it is what we did. Learning how to be a successful corporation required teaching our village leaders and new shareholders how the Western world of global businesses operated. Plus, we had no dollars, yet.”

That changed with a call that came in August of 1972. “I was out hauling in salmon and one of the other boats let me know the ANCSA money was available in Anchorage,” Jack recalls. “So, my crew handled the boat and I flew to Anchorage.”

With some seed dollars now in hand, Jack saw a steep educational curve. “As a Board, we learned a lot in the first years.” Wick continued, “All the original board members were fisherman. While there was a clear desire to help our people and shareholders on Kodiak Island, fishing was what we knew. But did we know how to make it profitable? No. We were still thinking in a subsistence manner.”

Through ANCSA, the federal government transferred 44 million acres of land to be held in corporate ownership by the Alaska Native shareholders of Alaska Native regional and village corporations. The federal government also compensated the newly formed Alaska Native corporations a total of $962.5 million for land lost in the settlement agreement.

The passage of ANCSA also created a land corridor for the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System. This helped move oil and gas exploration forward on the North Slope, where oil would be found in Prudhoe Bay. Afterward, construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System created thousands of jobs and pumped revenues into the state coffers, eventually leading to the creation of the Alaska Permanent Fund.

Janissa Johnson is a Director of the Koniag Board today who splits her time between Anchorage and Larsen Bay. She has known Jack all her life as a mentor and friend, and she considers him like family. “I am amazed at what Jack and other young fishermen achieved in getting ANCs off the ground, including my dad, Jimmy Johnson. To look back from half a century ago to where we are today, and to see how these Alaska Native leaders were able to forge a new path for Indigenous Alaskans, is breathtaking.”

As we look forward to the next fifty years of ANCSA, Jack puts it well: “You can’t stay under a rock, things change. There were some tough times, but we embraced the changes. I think the corporations are going in the right direction and…us old timers like me are proud of the corporations. I am proud of Koniag.”

Today, there are not many movie theaters open at all due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In Los Angeles, the Lakers have another basketball title, and we just finished a Super Bowl with one quarterback who is almost as old as ANCSA. But the mission of ANCs goes on, and as quickly as sports titles come and go, the needs of shareholders also change. “There are miles to go before ANCs sleep. The villages have changed, they are shrinking. We need to help continue our traditions and ties to the land,” says Jack.

Today’s leaders are still adapting and overcoming just as Jack did fifty years ago.